While significant progress has been made in pulmonary hypertension over the past few decades—ranging from new and better therapies to advanced interventions and surgeries—living with the condition still presents immense physical, emotional, and social challenges. The complex patient journey, often involving delayed diagnosis and lifelong management, takes a toll not just on the body but also on mental well-being.

Tackling the psychological challenges is crucial for holistic care and better health outcomes. This webinar explores the importance of mental health in pulmonary hypertension management, featuring experts who will discuss the role of mental health professionals, coping strategies, and ways to improve the overall well-being of PH patients.

Owing to technical issues, Sophia Esteves was not able to speak during the live session, so we recorded her presentation afterwards. This is the link to her presentation, which focuses on the many ways pulmonary hypertension affects mental well-being.

Transcript “Mental health issues in pulmonary arterial hypertension”

NB. This transcript can be translated into your preferred language – use the orange button at the bottom centre of this page to select it (slides are not translatable).

DISCLAIMER: Despite every effort to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, we strongly encourage all visitors to consult with their healthcare professionals before making any decisions based on the information provided. Additionally, while the quality of Google Translate has improved tremendously in recent years, please remember that it is an automated service and not a human translation.

ROBERT PLETICHA

Welcome to today’s webinar on mental health in pulmonary arterial hypertension. My name is Robert. I’m a project manager with admedicum, and I’ll be moderating today’s session. This is the sixth webinar in the series organized by the Alliance for Pulmonary Hypertension, a non-profit organization that is patient-led and promotes the exchange of knowledge and expertise around pulmonary hypertension and living with the condition. And that’s why we’re doing this series of webinars. You can see the other ones on our website as well as read the transcripts on the Knowledge Sharing Platform.

Mental health, today’s topic, is a really important one because I think over the years we’ve made a lot of progress in managing pulmonary arterial hypertension with new treatments and surgical options, which is what some of the other topics have been so far this year. But it’s important to recognize that the emotional and psychological impact of the condition can be just as challenging as the physical symptoms.

Mental health is a key aspect of holistic care, and addressing it can significantly improve the overall well-being of patients living with pulmonary hypertension. And so that’s why today we’ll hear from some distinguished experts in the field. First off, Prof. Karen Olsson, from the Hannover School of Medicine, Germany. Then Dr. Gregg Rawlings from the University of Sheffield, UK. And we also have Sophia Esteves, who has come to share her personal journey and the patient perspective about this important topic. So looking forward to an engaging and insightful discussion with you all. And please put your questions for our panelists in the chat box wherever you are watching us. So with that Prof. Olsson, please go ahead.

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

Thank you so much for the introduction. I’m, I’m very happy to be here, and I just want to, well, send some thoughts to Sandeep Sahay, who wanted to be here, but sadly his son passed away and he couldn’t leave to do the seminar with you. I think we can only assume what he’s going through, but not, not imagine. So we’ll just start the seminar, but our thoughts are also with Sandeep.

So just shortly, my disclosures. I’m working at the Hannover Medical School, and I’m doing a lot of diagnostics, invasive, non-invasive. And I often do the first diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. And I think when I do the echocardiogram, when I do the right heart catheterisation, even when you see smiling faces — so this is me and a patient who has done a lot of, a lot of caths — the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension, this means a lot. So if I meet the patient, probably he has gone through a lot of time of suffering, misdiagnosis. He’s been told “Well, just train some more. Just lose some weight and your dyspnea will get better.” And there’s a long way behind. And with the diagnosis there comes, on the one hand, the certainty that there is something that you are not simulating. But on the other hand, I think within a minute, there comes a lot, a big burden on the patient.

“Can I work? Can I have a family? Can I travel? Will I get old?” And you have to deal with severe dyspnea. Even doing your groceries or just going to the metro station will be a big problem. In the first years we just tried to, to keep our patients alive. And then over the last few years, we have had a lot of studies who told us that there’s really a lot of mental disorders in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or they’re severely mentally impaired after diagnosis.

Our studies on mental disorders began in the kindergarten, because the girl you see riding the bobby car of my son, was the daughter of our psychiatrist. I asked him, “We need to do something. We need to take care of the patients.” But, like a typical psychiatrist, he said, “No, we have to start even earlier” because when you have a look at all the studies they show up to 50% of the patients have depression or anxiety disorders, but all of them, they were done or performed with self-writing questionnaires, and not a clinical interview, which would be the gold standard.

So we implemented the “PEPPAH” study — well, at this time it’s clear where the name came from, not only, Peppa Pig, but in German this acronym means mental disorders and quality of life in patients with pulmonary hypertension. This was published some years ago in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

I’ll give you a short overview of what we found out with this study.

Defining the Problem

So the hypothesis was that pulmonary arterial hypertension is a rare and life-threatening disease. There was so far no cure at this time. The diagnosis is often delayed, it’s a progressive disease, and the fear of the future limitations in life, in working capacity, are definitely problems the patients are facing, and the development of a mental disorder should be obvious.

The existing studies, they were all based on self-rating questionnaires. We wanted to do have a large cohort, do a prospective and multicenter study, with validated questionnaires and a structured clinical interview, which is the gold standard. So we worked together with the medical school and University of Gießen and Marburg.

Together with Hannover, we had the two largest German pulmonary hypertension centers. And we were able to enrol 217 patients. We implemented parameters of clinical routine. We had lifestyle questionnaires concerning sports, alcohol, relationships. We also had standardised psychological questionnaires like the “Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale”, the HADS, or the overall quality of life, the “BREATH” score. And we had, of course, the clinical interviews, which were performed by a psychiatrist or our, well, trained students. And this is where we are now.

Results

The aim of our study was to see the prevalence of mental disorders in pulmonary arterial hypertension. We compared it to the general population in the same age, and we wanted to see the impact on quality of life, and we wanted to see the diagnostic value of the HADS score to identify mental disorders in pulmonary arterial hypertension. We saw that mental disorders were significantly more prevalent in patients with pulmonary hypertension.

You can see that about one-fourth of the patients had a major depressive disorder. And also a lot of patients, 15%, had a panic disorder. So more than one-third of the patients had at least one mental disorder, and there was a higher prevalence of depression, 23% versus 8%, and especially panic disorder, 15% versus 2%, so eight, three times or eight times higher than in the normal population.

We found out that about 38%, or almost 40%, also had an adjustment disorder after diagnosis, and approximately 50% of the patients with an adjustment disorder were in risk to develop any other mental disorder if the adjustment disorder was present. So an adjustment disorder is a maladaptive response on a psychological stressor. So I think it’s quite normal that you are under stress if you have such an impactful diagnosis and problems, but it depends on the, on the response if it is classified as disorder or just a normal reaction.

And, well, this next slide looks kind of complicated, but what it shows is that the quality of life is lower in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with mental disorders compared in all domains, as you can see, and depression, panic disorder, especially, you can see in this graphic.

Screening for Mental Disorders

So the question is, how can we detect mental disorders in our clinical routine? It would be very nice if all patients could undergo a clinical interview and psychological evaluation, but, as you all know, this is, this is not realistic because, even if patients who have a problem, it’s really hard to get psychotherapy or to get an appointment because resources are really limited.

We wanted to check if the HADS score maybe, as a simple diagnostic tool, could be used to identify patients who could need psychological support, and it showed a good correlation, so it is maybe a good and fast detection tool.

Conclusion

So in conclusion, mental disorders are common in pulmonary arterial hypertension, and they have a negative influence on quality of life. Mental health is an important part of pulmonary arterial hypertension and should be paid attention to. The HADS score may be used as a screening tool, and the future studies, I think, need also to address interventional strategies targeting mental disorders in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertensionand the access to psychological support.

I have brought you some additional slides, which are maybe some point of discussion for later on with Gregg. I’m not a psychologist, but we try to find a solution. We had a psychologist in our ward who was specialized in metacognitive therapy. So this is a little different to the usual cognitive behavioral therapy, and it addresses the metacognition in patients. We saw that metacognition, which means rumination and thinking too much about some things, are really different in our patients. So metacognitive therapy, we try to apply this in our patients, and it has the advantage that it’s only a few sessions, and it might help patients to get over at least the pathological ruminations on their disease.

This is just an example from the patient, or one patient we treated. She was always thinking about her disease and checking and checking and checking, and, with the metacognitive therapy, her thoughts were changed to “My body will tell me if it needs attention.” So the theory is that when there is a cognitive attention syndrome, which is characterized by inflexible attention, worry, and rumination, the coping then is dysfunctional, and the metacognitive therapy will discover this and can provide a solution or alternative.

Another aspect which we could discuss later on is work on the mental health. We did a study and, just in short words, we saw that, of course, there was a strong association between quality of life, education and employment status, and the physical condition. Of course, patients who had a bad physical condition weren’t able to work, and the educational status, of course, goes hand in hand with physical work or mental work. And so, of course, physical work is much harder to remain in or to achieve if you’re physically impaired. And what we saw is that employed patients had significantly better quality of life. And if you go into detail, I think the best quality of life were in patients who had a part-time job, enough time to take care of their health but also be able to work and to contribute.

Sotatercept

We have had a milestone in the last years or months with the development of sotatercept, and what we saw in the clinic was that we had the feeling that for patients everything will get better, like mental health will get better anyway, but it didn’t. We had so many contacts and so many other problems. And so we did the same what we did before.

We had 20 patients who had participated in the first trial and who had at least six months of sotatercept. The prevalence of mental disorder was comparable. There was no change in metacognitive beliefs. We had a higher prevalence of general anxiety disorder or adjustment disorder. What we did see in our questions, was that sotatercept influences patients’ outlook, hope, and lifestyle. It had a multifaceted impact on both physical and psychosocial aspects. So many problems, e.g. “Will I be able to keep social security?” We had some patients whose partnerships ended because the partner finally said, “Well, you are well now. I don’t need to take care.” And we had some patients who had, were who felt guilty because they had sotatercept and others weren’t able to enter the study.

I think here we have really a lot of new challenges, for both for us but also for the patients who have a completely new perspective and who need to change their life and maybe in the other way around or to define themselves anew. And I hope that we will be able to address that, maybe with the help also of the companies or, because I think the healthcare situation concerning mental health is really limited, and so maybe we’re able to empower the resources. Thank you very much.

PROF. GREGG RAWLINGS

First of all, thank you very much for having me, and I’m delighted to be here to talk about some of the research I’ve been doing in collaboration with Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK, PHA UK, the only dedicated charity in the UK for people with pulmonary hypertension.

My name’s Gregg Rawlings. I have a Master’s degree in Psychology and a PhD in Neuroscience. I completed my doctoral training in clinical psychology in 2021, so I’m a clinical psychologist working in the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. I’m also a lecturer in Clinical Psychology at the University of Sheffield. My involvement in pulmonary hypertension is in research, so I don’t work clinically with this patient group. I work in the National Health Service with adults with a learning disability in my clinical role, but in my research role I have collaborated with the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK and colleagues from Sheffield Teaching Hospitals in a range of research projects involving individuals with pulmonary hypertension as well as caregivers, and that’s some of the work I’m going to be presenting today.

I’ve decided to split my talk into three sections. The first one is defining the problem, and I just want to kind of expand on some of the points that Prof. Olsson has been discussing. Then I want to move on to “What do we know about the problem?” before moving on to “What, what are we doing about the problem?” And this is a cyclic, so the idea is that it’ll then feed back into defining the problem and furthering our understanding.

Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression

The first thing I just wanted to display was this graph here, which was published a few years ago by my own colleagues. It is a meta-analysis, a systematic review looking at the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people with pulmonary hypertension.

Anxiety and depression has probably been looked at the most as mental health conditions in pulmonary hypertension, for different reasons. One reason might be is there’s quite an overlap between symptoms of anxiety and depression and pulmonary hypertension, but this study looked at 24 studies, and it involved data from over 2.000 patients with pulmonary hypertension. And as you can see, the rates of anxiety and depression are very high: on average, around 28% of people reported clinical levels of depression, and around 37% report clinical levels of anxiety. So very, very high rates, and, as Dr. Olsson was saying, higher than what would expect to see in the general population, in other words higher than what we expect to see people without pulmonary hypertension.

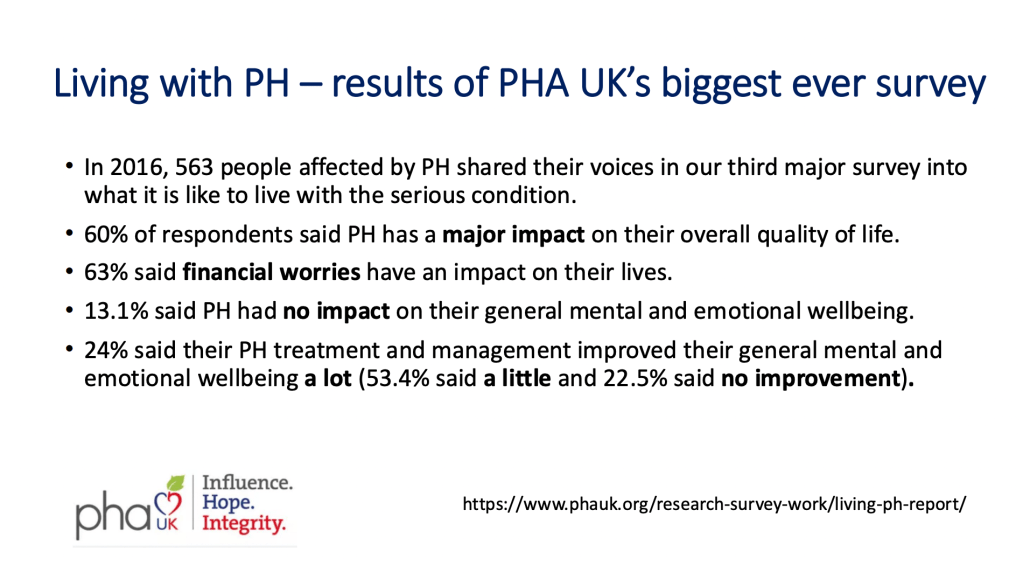

Thinking about the UK, for example, in 2016 the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK conducted the biggest survey they have ever done of experiences of living with pulmonary hypertension. And as you can see, 563 people contributed to the survey, and these are just some pull-out findings I wanted to display. 60% said pulmonary hypertension had a major impact on their overall quality of life. Dr. Olsson has already mentioned the relationship between pulmonary hypertension and reduced quality of life. 63% said financial worries had an impact on their lives. So some examples of some specific difficulties. 13% said pulmonary hypertension had no impact on their general mental and emotional well-being. The vast majority reported that pulmonary hypertension had an impact on their mental and emotional well-being. 24% said their pulmonary hypertension treatment and management improved their general mental and emotional well-being a lot. In comparison, 53% said only a little, and 22% said no improvement. So that would suggest that there is certainly a need to think about the mental health and well-being of individuals with pulmonary hypertension.

Predictors of Anxiety and Depression

Moving on to “What do we know about the problem?”, this table is taken from my paper that I mentioned earlier, and this is looking at predictors or risk factors for anxiety and depression in people with pulmonary hypertension. And essentially what you’re looking at there is you’re looking at the P-value, and anything below the 0.05 would suggest that it’s significant. So, as you can see here, none of the demographic factors are a significant risk factor for depression, anxiety. That would suggest that regardless of age, gender, ethnicity everyone could be at risk of anxiety and depression in pulmonary hypertension. The next thing is around diagnosis, and the final thing is around severity.

I just wanted to draw your attention to this, and this is looking at severity of pulmonary hypertension, and this is looked at through the World Health Organization (WHO) functional class. And as you can see here, severity as measured by the World Health Organization functional class is not a predictor of depression or anxiety, so it’s not a predictor of depression, anxiety. So this led us to believe that available studies indicate that disease-specific factors alone are unable to fully account for the reported impact, and physiological measures of functioning tend to be non-significant risk factors for depression and anxiety. That would suggest that there’s something else at play, something that we need to think about in terms of the higher risk for development and depression, anxiety in pulmonary hypertension.

Psychosocial Factors

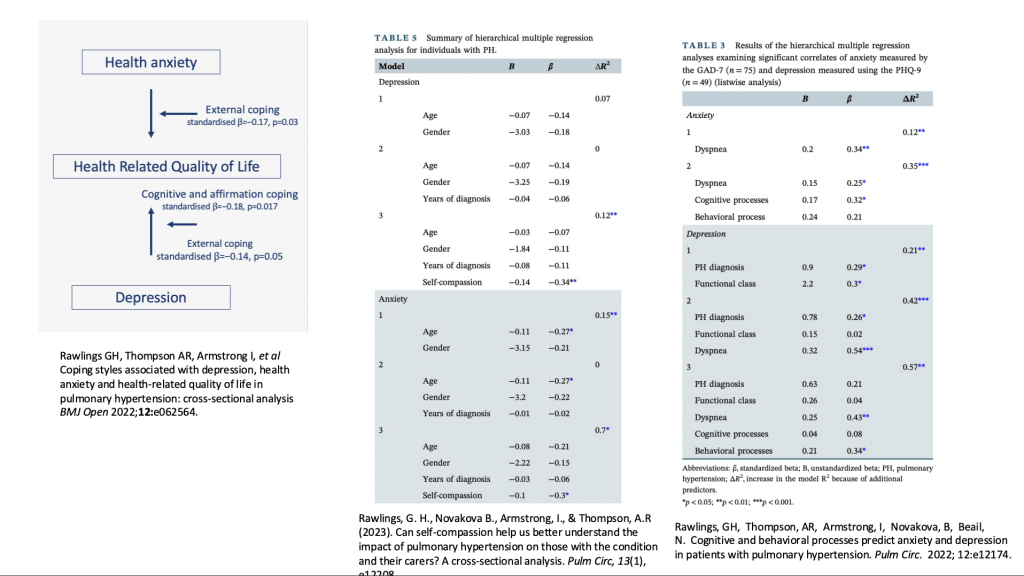

We’ve been doing a range of studies looking at psychosocial factors to see whether they could help us to understand the high rates of anxiety and depression in this population, as well as the reduced quality of life. And these are just a few papers that we have completed and since published.

The first one is looking at the relationship between anxiety and quality of life and depression and quality of life, recognizing that higher anxiety and depression would reduce health-related quality of life. But what we were able to find is things like external coping, so essentially coping skills, were able to moderate that relationship, so it was able to weaken that relationship. And that’s important because that could highlight a therapeutic target. If we can think about how people are coping with things like anxiety and depression and pulmonary hypertension, then maybe we can also help to improve the quality of life as well as manage anxiety and depression symptoms.

The middle table is looking at things like self-compassion, so how compassionate someone is to themselves, to see whether that could help to predict anxiety and depression. And we found that yes, it’s, it is a predictor, so self-compassion might be a therapeutic target.

And then the third table was looking at predictors of anxiety and depression, looking at cognitions. This is about our thinking patterns and behaviours, what we do, and we found was that cognitions were more related to anxiety, whereas behaviours were more related to depression. And, again, that can help us to think about therapeutic targets.

So, if we’re working with a patient who’s presenting with anxiety, what we might want to focus on is cognitions, thinking patterns. Whereas if we’re working with someone who’s experiencing depression, we may want to think about more about the behavioural targets. So, again, that’s just a very brief overview of some of the work that we’ve been doing. Now we’re moving on to the third point.

Psychological Interventions

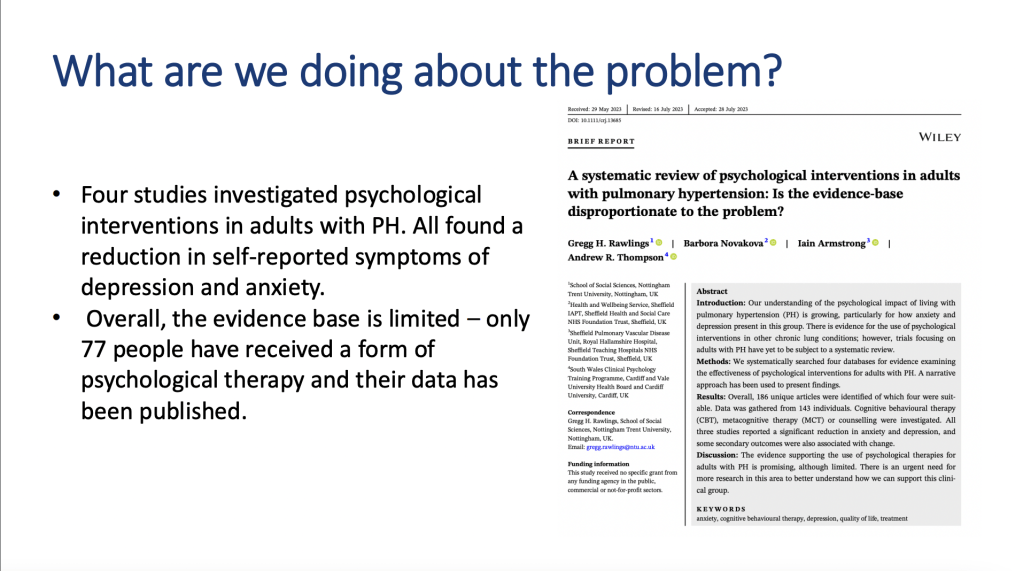

What are we doing about the problem? We recently did a systematic review of the evidence base looking at psychological interventions in pulmonary hypertension, targeting mental health difficulties.

We found four studies in total — one of them Dr. Olsson has already mentioned — and we found that all trials were associated with a reduction in self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. So that suggests that there’s some evidence to suggest psychological therapies are helpful for this patient group. However, what we also found was the evidence base is limited, and the evidence is only available from 77 people who have received a form of psychological therapy, and the data has been published. Again, this led us to ask “Is the evidence-based disproportionate to the problem?” So, recognizing the high rates of anxiety and depression in this population, and actually, when we look at the trials, looking at psychological interventions targeting anxiety and depression, it seems to be there’s a, there’s a mismatch between the two.

Self-Help Intervention

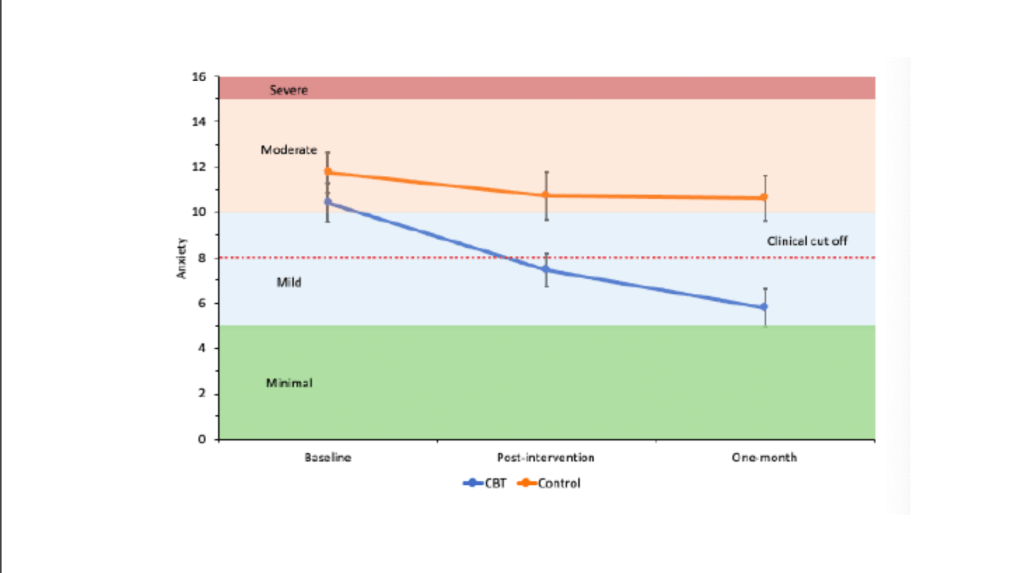

Based on cognitive behavioural therapy, one of the trials included in that systematic review is one of our studies, and this is where we developed and evaluated, using a pilot randomized controlled trial — and I’ll explain what that means in a minute — a self-help intervention based on a type of therapy called cognitive behavioral therapy or CBT, and this targeted anxiety in pulmonary hypertension. And our trial involved 77 adults with pulmonary hypertension.

So this is what it looked like. So we had 77 people who were randomized to either receive the self-help intervention, or they were randomized to receive or not. So this means they didn’t receive any, any intervention in terms of our CBT self-help, but they did receive it at the end of the intervention. And the intervention itself is self-help, so this means that people completed at home at their own time in private, and there were four sessions or four weeks, which corresponded to four booklets. And each booklet, as you can see, had different contents and, and different exercises. And this was based on cognitive behavioural therapy, so this was a, a four-week intervention.

We measured anxiety using a screening tool known as the GAD-7, the “Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven-tool” questionnaire. And we asked people to fill out this questionnaire before receiving the intervention, after the intervention. This was four weeks after, and then one month after that, so eight weeks after starting the intervention. And what this graph here shows is, as you can see, there’s two lines. There’s one in orange, and this is known as our control group. So individuals randomized to that group didn’t receive any intervention, whereas people in the blue line were randomized to receive the intervention, the cognitive behavioural therapy intervention. And as you can see at baseline, they both scored within the moderate range of generalized anxiety disorder, then, at the post-intervention, so after the intervention, people in the cognitive behavioural therapy group reported mild symptoms, whereas those in the control group continued to report moderate symptoms. But also what’s really important is that the GAD-7, the tool that we used, has a cutoff, and the cutoff is eight. So this means that if you score above the cutoff, it would recommend, or it might suggest that you may benefit from receiving additional support. And as you can see, people in the cognitive behavioural therapy group scored under that cutoff on the post-intervention. And then one month later, they continued to make improvements, and they continued to be under the cutoff. Recognizing the link, or the overlap or the high correlation between anxiety and depression, we also measured depression.

So we used the PHQ-9, the “Patient Health Questionnaire”, which is a validated tool for screening for depressive symptoms. And, as you can see, we found very similar results. So people in the cognitive behavioural therapy group reported a reduction into the mild and continue to steer below that cutoff. So it’s important to recognize that was a pilot randomized controlled trial, which means that it it is not a definitive randomized controlled trial. That means that we needed more people in the trial to say with a high level of certainty that these results are an accurate reflection of what we found. Nevertheless, what it suggests is that it is preliminary evidence for its effectiveness.

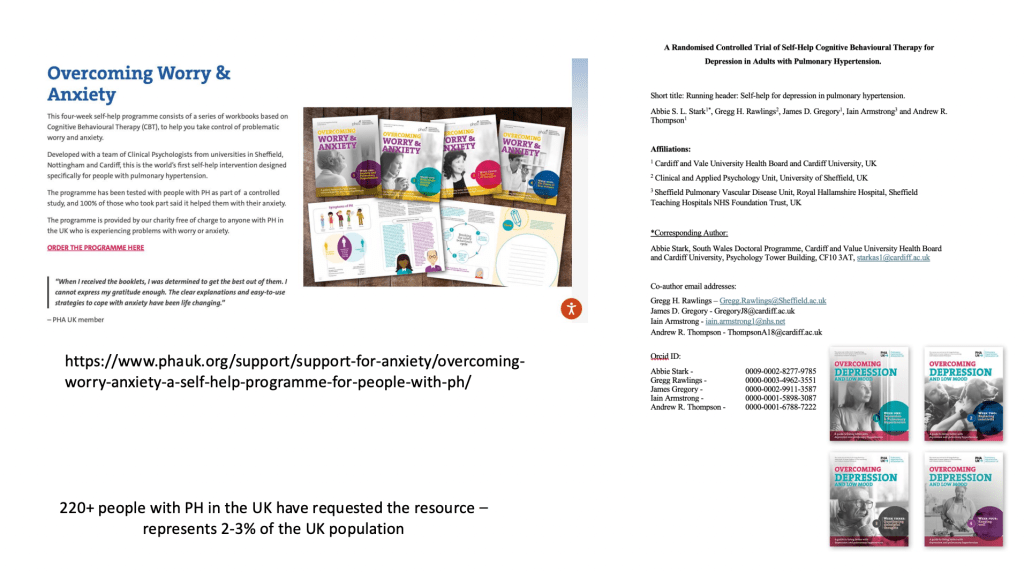

Cognitive behavioural therapy booklets

We developed and tested the intervention and we published the intervention and since made it available via the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK, PHA UK, to all members, free of charge. As of August 2024 over 220 people have requested the intervention. So when we look at kind of the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in the UK, this would represent around 2-3% of the population that has requested the booklets. What we’ve also done is we’ve expanded on that idea, and we’ve developed booklets looking at depression, and this is exactly the same idea: four weeks, four booklets. And we’ve since tested this in a randomized controlled trial, and we’ve analyzed the results, and we’ve submitted for publication, and we’re looking forward to sharing the results with, with the wider community when it’s appropriate.

Ideas for Future Research

So, those were my three points: 1) defining the problem, 2) what do we know about the problem, 3) what are we doing about the problem? Based on the evidence from our research, these are some ideas that I have came up with that I think would be useful for future research. The first is to continue to identify what factors are associated with anxiety and depression. We can also think about looking at other mental health difficulties in this population, recognizing that most of the evidence has been looking at anxiety and depression. Also we need to think about how we can best identify people with pulmonary hypertension at risk of mental health difficulties. I know Dr. Olsson was already mentioning this. Thinking about preventative strategies, and also when people do score above a cutoff, for example, think about how depression and anxiety interact with pulmonary hypertension specifically. And also thinking about groups who are currently underrepresented within the evidence base. And think about developing strategies to help people with depression and anxiety, and these can be standalone interventions as well as integrated care.

Finally, think about mental health difficulties in non-professional caregivers. So, for example, we’d done a study looking at rates of anxiety and depression in people with pulmonary hypertension and their caregivers, and we found no significant differences in rates of anxiety and depression, so rates are high in non-professional caregivers just as are they high in this patient group.

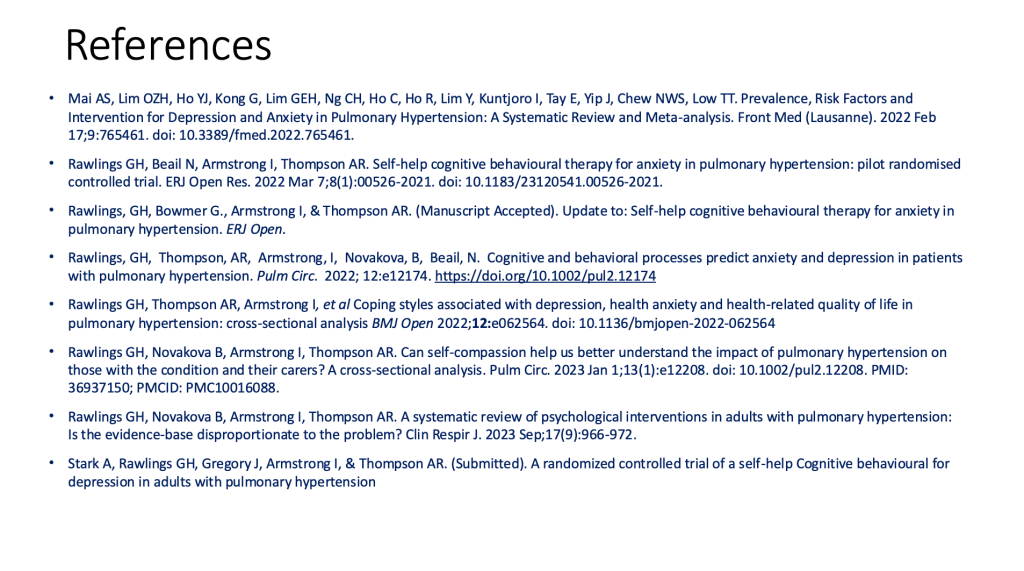

I would like to thank my colleagues, and the next slide is my references, and that’s the end of my presentation. Thank you very much for your time.

ROBERT PLETICHA

Thank you very much, Dr. Rawlings, and I like how you ended with ideas for already thinking about the next research projects. I want to first, before I ask some questions, give the floor back to Dr. Olsson to see if she has any reactions or questions for Dr. Rawlings.

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

I have a lot of questions or comments, Gregg. So, given that I think the waiting time for psychological interventions is often between six months and a year, and we have seen that addressing it right at the beginning is useful to prevent our patients from having add-on psychological or mental problems, have you also considered artificial intelligence? Our colleagues are working on an app-based psychotherapy. Have you, have you thought about this or implemented your interventions also via app, or do you have translations for that so that it could be used internationally?

PROF. GREGG RAWLINGS

Yes, absolutely. The way we tested the intervention was that people in the UK who signed up to the intervention received a paper version of the booklets, whereas people outside the UK, received an electronic version of the booklets. Due to sample size, we weren’t able to compare whether both were effective or whether one is more effective than the other, so that’s something to consider. There’s lots of online resources out there, and I think the adoption of some of our resources about anxiety and depression could convert very well. One of the drawbacks – we asked people’s views on the booklets as well – was there’s some fantastic resources out there, things like videos and self-help, and we could signpost people to those resources. And if it was all on one app, you know, click the button, you could be directed to a help resource. So we are looking of making an app and putting a lot of the resources and Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK, PHA UK, also have a great deal of resources as well. So if you could make it readily available that would be fantastic. And I suppose one of the ideas is to reduce barriers to accessing support, whether that is due to resources or whether it may be due to other things like the stigma of asking.

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

Do you often face this? I ask because we did not have many dropouts and it wasn’t difficult to recruit, but, for example, Mélanie, in the comments says that it’s often a barrier and that there is a lack of acceptance that one needs psychological support. Did you face that or did you recognize that? Because what I think when talking to the patient, is that maybe one can be stigmatized as having a mental disorder for years rather than diagnosed having pulmonary hypertension and maybe there’s a problem to accept that there’s both, or maybe it’s not, it’s the impact of pulmonary hypertension, which causes it also.

PROF. GREGG RAWLINGS

Yes, absolutely. And I think this is so. In the booklets during the first week we were focusing on what we call “psycho-education”. It’s about educating people around symptoms of anxiety and depression, thinking about how the tool can overlap, normalizing a lot of these experiences and thinking about prevalence rates. I think that can be a really helpful way of normalizing and recognizing you’re not the only one. What we also did was we created some fictional vignettes to kind of carry through the booklets that people may be able to identify some of their own experiences, some of their own difficulties. We’ve also recently reviewed the literature looking at what people said about living with pulmonary hypertension. And one of the things that came up was the rarity of the condition, and that can impact where you get resources and how people respond to you, even within medical settings.

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

Just one comment, if you want to treat pulmonary hypertension, you have to take care also of nutrition, physical exercise and medication. Mental health is just one thing, and I often refer to it as kind of “coaching” because it’s not like have to need some expert tips. You also accept them if you need physiotherapy, for instance, and then sometimes you just need some, some flips to get over.

Pisana and Eva just wrote in the comments that in Italy and in Austria psychotherapy was offered at the time of diagnosis, but it was not well accepted. That’s really interesting because I often have the feeling that we are addressing it kind of aggressively. And we rather have the problems that the access to psychotherapy is the problem because we, we just mentioned it right from the beginning, like many things you have to have to have to cope with, like quite a normal thing that you have to address. And I think we have the excess problem, but was it long ago or was it recent? Tiana and, and Iffa, maybe

ROBERT PLETICHA

Meanwhile, also Sophia shared a comment that diet is a big part of it. A lot of patients are getting very depressed when they have to rest and rest

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

Yeah, that’s def definitely a problem if you, if you can’t move, you gain weight, you get, it’s like a vicious cycle. you circle, you’re in. Yeah, I, I that’s really, really also a good point. So Sophia’s just telling us that she had, she was living with pulmonary hypertension for 23 years and had over 20 heart catheterisation, so that is worked a lot of downtime. Yeah,

Maybe let’s also something we, we can try to address in medicine. I think there’s a lot of movement towards ambulatory medicine to reduce downtime for the patients, or if you have like cervical access, you can just get up like a few minutes later after the cast in, in contrast, if you if you have a catheter through the groin, and maybe this, that also adds to quality of life too. do everything as, as less invasive or with, with the least downtime and intervention in, in the normal life.

ROBERT PLETICHA

Dr. Rawlings, I was wondering from a practical standpoint, if someone wanted like a patient association as we have many listening, if they wanted to look into translating the, the booklet series, would they contact you or PHA UK to begin that conversation?

PROF. GREGG RAWLINGS

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. contact the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK, PHA UK, so that, that they’re the ones who funded the, the, the trials. and they hold the copyright for, for, for the resources. But we’ve had other pulmonary hypertension organizations around the world contact us, ask whether they can start to adapt or translate and yeah, absolutely, very, very keen to, to share resource. So please, please contact them.

ROBERT PLETICHA

Great. Thanks so much for that. And yeah, Pisana add, even a six minute walk test can be stressful as, you know, kind of leading up to it. anxiety can build Melanie is saying that’s true and for some, you know, they fear not doing well enough on the test. So a good conversation going in the comments. And Sophia also mentions here in the chat that some patients are intimidated by the gym because they walk in short of breath. Sophia ha has to take her oxygen tanks with her to the gym, and they’ll be active in some capacity, but getting approved for oxygen is yet another challenge. Good point Sophia, I’ll contact you after this and we’ll find a time to rerecord your part so that we can publish it alongside this webinar.

But yeah, I think we’ve, we’ve done well for today and we’ve covered a lot and we’ve had some really great presentations. yeah, shame again that we couldn’t hear from Sophia, but thanks again for trying and for being here. Thank you also to Dr. Rawlings and Dr. Olsson for sharing your research and for making sure that this is an issue that people don’t just forget about or is swept under the rug. But even if there is some stigma attached to it, you’re out there and researching it and trying to shine some light on it and understand it and kind of point out, you know, that there’s a problem and we need to do some interventions to try to stop that. So any other last words from our panelists?

PROF. GREGG RAWLINGS

No, no, nothing from me other than yeah, thank, thank you very much for, for inviting me.

PROF. KAREN OLSSON

Yeah. I would maybe just also thank you and say that such comments such as Sophia just made that you’re afraid of the six minute walk. We also have to learn as physicians, I had to learn that also that the anxiety to go to the appointment, “will I perform well”, “will I do that well”, is very important. So we, we are trying to do the outpatient clinic as, as nice as possible. And sotatercept has made has, has taught us something because people were coming every three weeks with the same patients. And that was really good because they were, it wasn’t like a medical visit. It was like meeting friends, just doing the, the study stuff besides, and there were really groups and coffees and everything and I think we, we have to work together and we have to have to focus on that and we need the patient input or just to learn how we can improve also our performance with simple things. Maybe just us meeting the same people for a coffee in the pulmonary hypertension clinic.

ROBERT PLETICHA

Yeah, sometimes it’s that simple. And that sounds like a really nice space you’ve created there and one that most people would love to take part in and Sophia says, yes, or pulmonary rehab clinic could be a great approach to getting patients interested in how to live a healthier life. So taking that opportunity from there at the clinic. Great point, Sophia. So no, thank you all for joining and thanks again to our panelists for your excellent presentations and this recording and the slides will be up on the knowledge sharing platform of the Alliance for Pulmonary Hypertension in just a few days. So check for it there. And our next webinar will be in November and it’ll be our first one in Spanish, so we’re very excited for that. And stay tuned for more details on that. Thanks everyone, and have a good evening.

SOPHIA ESTEVAS (recorded after the webinar for technical reasons)

Hi, my name is Sophia Estevas, and I am a patient advocate for pulmonary arterial hypertension. I am also a support group leader, and today I want to talk to you about mental health. Mental health is becoming more of a concern in our community, so I wanted to share some feedback and input I’ve received from our community.

I am also a patient myself. I’ve lived with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) for 23 years now. Looking back, I remember how life-changing the diagnosis was—it felt so heavy. Depending on when you were diagnosed, you might have been given a specific timeframe for how long you were expected to live. For me, I was told I had four years to live. At the time, I was only 21 years old and was told I needed to stop working. It was very hard for me to comprehend my next steps.

The Importance of Holistic Care

For the future, I imagine patients receiving a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis being referred to a therapist and a dietitian. No one is prepared for such a heavy diagnosis. It would help to have someone who could follow along on this journey and provide reassurance, guidance, and support.

Diet is another significant factor. With heart failure or medication side effects, a low-sodium diet is often recommended. This can be challenging, especially if it’s different from the diet you grew up with. Meeting with a dietitian could help patients identify foods that benefit their bodies while living with pulmonary arterial hypertension. A healthy lifestyle is still achievable with the right guidance.

I also imagine pulmonary arterial hypertension centers bringing therapists or dietitians in-house so that as patients receive their diagnosis, they are referred to professionals who work closely with their doctors. This collaboration would be incredibly beneficial.

Treatment Options and Challenges

Treatment options are another area where many patients struggle. It’s hard to imagine life with a large, visible pump or other medical devices. Many patients feel overwhelmed with questions such as:

- Am I choosing the right treatment?

- How will this affect my appearance?

- How can I exercise or maintain intimacy with my partner?

Unfortunately, current treatment devices are often large and difficult to conceal, which can impact patients’ confidence and privacy. I hope future advancements in treatment will consider the size and design of these devices to give patients more options for a discreet and manageable life.

Side effects from treatments are another challenge. These can include nausea, diarrhea, headaches, jaw pain, and nerve pain. It’s a lot to cope with on top of managing pulmonary arterial hypertension itself. Patients are taught to treat the side effects while staying on their PAH medications, which can feel overwhelming. Managing side effects often means dealing with downtime when you simply can’t function as planned. This can lead to a sense of guilt, especially for those with responsibilities such as work, caregiving, or parenting. It’s essential to learn to prioritize yourself and set boundaries.

Acceptance and Mental Health

Living with pulmonary arterial hypertension also involves accepting areas of disability. For instance, using a handicap parking spot can invite discrimination when your condition isn’t visibly apparent. Educating others about pulmonary arterial hypertension in these moments can help create understanding and awareness.

Pregnancy is another sensitive topic, especially in a community with many women. Being told you can’t have children is a life-altering realization that requires acceptance. Some women have successfully carried to term, but it’s not generally recommended due to the risks. Options like adoption or surrogacy have brought joy to some families, but the journey involves a lot of acceptance.

Maintaining Relationships and Social Support

Intimacy is a common concern among patients, especially when managing medical devices or side effects. There are different ways to maintain intimacy, such as exploring new types of connection, taking trips, or simply spending quality time together. A fulfilling relationship is still possible with some adjustments.

Social groups can be challenging to navigate with an invisible illness. Explaining pulmonary arterial hypertension to others who may not understand can create mental health struggles. Patients often feel they’re letting others down when side effects prevent them from fulfilling commitments like work or social obligations.

Work: For many, disability becomes a necessary path. Some patients have to stop working entirely, especially if they’re preparing for a lung transplant, which requires significant time and recovery.

The Importance of Transparency and Advocacy

If you’re a patient, I encourage you to be transparent with your family, friends, and groups. Sharing what you’re going through allows others to understand and help. People often want to help—they just need to know how.

Find your community. Support groups can offer a safe space where you’re understood without judgment. Even if you can’t attend every session, the door remains open. Creating healthy boundaries is also essential. Learn to say no when necessary and schedule your life in ways that accommodate your condition. For example, I avoid scheduling early morning appointments because I know I won’t feel well at that time.

Communication with Doctors and Advocates

Maintain open communication with your doctors. Discuss what medications work for you and align with your life goals. Don’t hesitate to ask about alternative treatments if your current plan doesn’t suit your lifestyle. Patient advocates, like myself, are also here to help. We can provide guidance and connect you to resources, whether through online platforms or local groups.

Living a Healthy Lifestyle with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Exercise can feel daunting, but it’s possible with the right support, like prescribed oxygen. Start small, and focus on what feels manageable. A healthy lifestyle includes regular exercise, a balanced diet, and mental health care, all of which contribute to a better quality of life.

Closing Thoughts

In summary, living with PAH involves many layers: managing treatments, dealing with side effects, navigating relationships, and maintaining mental health. It’s crucial to find your support system, establish healthy routines, and focus on what you can control.

There is hope. Life with pulmonary arterial hypertension can still be fulfilling. By accepting what we cannot change and taking proactive steps toward what we can, we can live meaningful lives. Thank you for listening, and I wish you all the best on your journey.