“ADVANCING CTEPH CARE: EXPLORING THE MULTIMODAL STRATEGY IN THE NEW ESC/ERS GUIDELINES”, November 21, 2024

NB. This transcript can be translated into your preferred language – use orange button at the bottom centre of this page to select it (slides are not translatable).

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN, MODERATOR

Today, we’ll delve into chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, a rare type of pulmonary hypertension. I’m honored to be joined by two distinguished experts in this field: Professor Marion Delcroix, from the UZ leuven Belgium, and Professor Xavier Jais, from Paris Hospital. We will begin with presentations from our experts. Afterwards, there will be an opportunity for you to engage by submitting your questions and comments in the chat. I’m eager to incorporate your insights into our discussion. Let’s start with Professor Marion Delcroix.

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

Thank you for that introduction. I will begin by discussing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension up to the point of diagnosis, after which Javier will cover treatment options.

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is a subset of pulmonary hypertension, classified within the fourth group of the World Health Organisation pulmonary hypertension classification system. By definition, it is a form of pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension, characterized by a mean pulmonary artery pressure exceeding 20 millimeters of mercury (mg), alongside normal pulmonary artery wedge pressure. Diagnostic imaging plays a crucial role, with ventilation-perfusion scans revealing mismatched perfusion defects, and computerized tomography scans or angiography displaying distinctive chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension findings, which I will illustrate later.

To differentiate this disease from acute pulmonary embolism, a standard practice is to observe the patient under anticoagulation therapy for three months. During the latest guidelines meeting, the concept of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease was introduced to acknowledge patients who exhibit similar symptoms and imaging findings but do not meet the criteria for pulmonary hypertension, possibly developing it only during physical exertion.

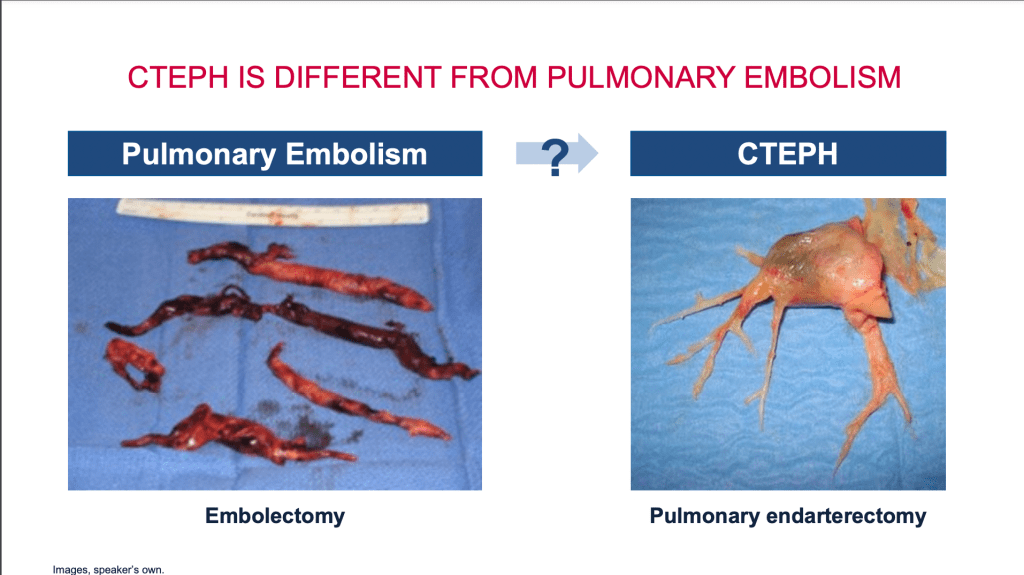

Registry data indicates that approximately 75% of these patients have a history of acute pulmonary embolism, often stemming from deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs. The clots travel to the lungs, lodging in the pulmonary arteries. While the majority of patients’ bodies can dissolve these clots, about 3% transform into fibrotic material, requiring a different treatment approach. Pulmonary endarterectomy surgery is a significant treatment for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, effectively removing these fibrotic clots from the pulmonary arteries, as demonstrated in the surgery results I will share.

In this disease, we observe what can be described as a three-compartment model involving the pulmonary arteries. The first compartment involves obstruction near the heart in the large pulmonary artery. The pulmonary arterial system resembles a tree, where these large arteries resemble main branches. As we move further along, we encounter the second compartment: the smaller branches. Finally, the third compartment consists of the very small vessels, comparable to the leaves of a tree, known as the microvascular circulation. This smallest compartment can also be affected by disease, mirroring the pathological changes seen in pulmonary arterial hypertension.

As previously mentioned, approximately 3% of patients, or more precisely 2.7%, who experience an acute pulmonary embolism will later receive a diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. This incidence rate increases in cases of idiopathic embolism, where the embolism occurs without any apparent cause or preceding immobilization. Furthermore, the risk of developing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension escalates threefold in patients who experience recurrent venous thromboembolism. The risk increases dramatically, up to sevenfold, translating to a 21% chance, in individuals displaying any signs of right ventricular dysfunction, characterized by a dilated and poorly functioning right ventricle.these studies were on more than ten thousand patients.

Patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension are often initially identified through an acute pulmonary embolism episode. Given the frequency of acute embolism, it’s crucial that patients receive comprehensive evaluations through echocardiography and computerized tomography scans at the onset of these acute episodes. Identifying pulmonary hypertension during this acute phase can serve as an early indicator that the patient may have previously experienced unrecognized and untreated pulmonary emboli, which have now progressed to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

The significance of acute-phase imaging extends to radiological examinations, where detecting signs of chronic obstruction and a dilated right heart is paramount. Recognizing these indicators of chronic vessel obstruction requires expertise; it is a task that demands a seasoned radiologist or a pulmonary hypertension specialist. The subtlety of these signs means that without a careful and knowledgeable assessment, there’s a high risk of misdiagnosis.

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is a rare condition that is likely under-diagnosed, with registries indicating an annual diagnosis rate of six patients per million, threefold higher than that for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. However, with acute pulmonary embolism’s incidence, and a 3% progression estimate to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, the expected diagnosis rate could be as high as 17 cases per million annually, suggesting a significant under-diagnosis issue. Evidence from Sheffield, UK, supports this, where diligent patient tracking revealed a diagnosis rate of 12 cases per million per year.

The development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension following a pulmonary embolism is a complex process influenced by various factors. These include:

1. Abnormal Clot Formation and Dissolution: The basis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension lies in the improper formation and inability to dissolve clots properly within the pulmonary vasculature. This abnormal clotting can be exacerbated by genetic anomalies in coagulation pathways, making certain individuals more susceptible to forming persistent clots that can lead to the disease.

2. Inflammation and Infection: inflammation, whether as a part of the body’s response to the initial embolism or due to other causes, can contribute to the disease’s progression. Infection may also play a role, potentially acting as a trigger or exacerbating factor for clot persistence and vascular damage.

3. Role of the Spleen: The spleen’s involvement highlights the importance of the immune system in managing blood clots. Patients without a spleen are at an increased risk of developing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension , suggesting that the spleen may play a protective role in clot management and resolution.

4. Genetic Factors: While specific genetic anomalies related to coagulation can predispose individuals to abnormal clot formation, the exact relationship between these anomalies and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is still under investigation. These genetic factors could influence the likelihood of clot persistence or the severity of the disease.

5. Vascular Remodeling and Microvascular Pathology: The persistence of large clots, composed primarily of fibrotic material, leads to the obstruction of major pulmonary vessels. This results in increased pressure and blood flow to non-obstructive lung regions, which can induce vascular remodeling—similar to what is observed in idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. This remodeling involves the thickening of small vessels and is a hallmark of disease progression in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension . The altered flow and chronic high pressure contribute to further vascular damage and microvascular pathology, exacerbating the disease.

Here we can tell the importance of thorough follow-up and investigation in patients presenting with acute pulmonary embolism . Identifying those at risk of developing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is crucial for early intervention and management, aiming to prevent disease progression and improve patient outcomes. Understanding the mechanisms underlying this disease is essential for developing targeted therapies and improving the prognosis for patients with this condition.

Symptoms of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

- Shortness of breath during activities (e.g., climbing stairs)

- Leg edema

- Fatigue

- Syncope (less frequent)

- Hemoptysis (rare, coughing up blood)

Diagnosis Delay: Time from symptom onset to diagnosis often >1 year, based on data from ~700 patients.

Improving Diagnosis Time: Diligent follow-up of acute pulmonary embolism patients could shorten this duration

Structured Diagnostic Approach for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Start with identifying individuals at risk, especially those referred for pulmonary hypertension.

Initial Diagnostic Tool: Ventilation-perfusion scan to reveal mismatched perfusion defects indicative of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Exploring Alternatives to Traditional Imaging: Research into dual-energy scans and iodine subtraction methods for detecting perfusion abnormalities. These alternatives are not yet universally validated.

Evaluation for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension Post-Acute pulmonary embolism: Patients with persistent or new-onset symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath, exercise limitation) after an acute pulmonary embolism are evaluated for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Guideline Recommendations: Tiered recommendation system with Class 1 being strong recommendations based on evidence or expert opinion.

Diagnostic Process: An abnormal ventilation perfusion scan leads to referral to a specialized chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension center.

Comprehensive assessment includes echocardiography for pulmonary hypertension screening and stress tests for symptom evaluation during exercise.

Further diagnostic confirmation at chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension centers includes: right heart catheterization and advanced imaging to ascertain the presence of pulmonary hypertension and vascular obstructions.

Treatment options: Dr. Jais will give you a detailed approach later only to emphasize that fifteen years ago we had only surgery, but today we have: surgery (pulmonary endarterectomy), balloon pulmonary angioplasty (2012), medical therapy, or a combination of both, emphasizing the role of a multidisciplinary team in management decisions.

The establishment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension centers underscores the necessity for specialized care, adhering to quality standards and ensuring patient education and empowerment.

These centers are characterized by a collaborative team of healthcare professionals experienced in managing pulmonary hypertension and related interventions.

The Open Lung Foundation’s guidelines for patients highlight the importance of expert care teams and the need for treatment facilities to meet specific volume and quality metrics to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

In conclusion

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is a complex condition with varying etiologies and manifestations.

Early recognition and specialized care are crucial for effective management. Despite challenges in diagnosis, advancements in imaging and treatment approaches have significantly improved patient prognosis.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Thank you very much, Dr. Delcroix, for your insightful and comprehensive presentation on pathology. A few questions have arisen from your presentation, but before we address them, let’s turn to Professor Jais. He will discuss the multidisciplinary and multi-professional approach. Dr. Jais, please feel free to share your screen when you’re ready.

DR. XAVIER JAIS

Thank you. Good afternoon, everyone. It is my pleasure to present the management strategy for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

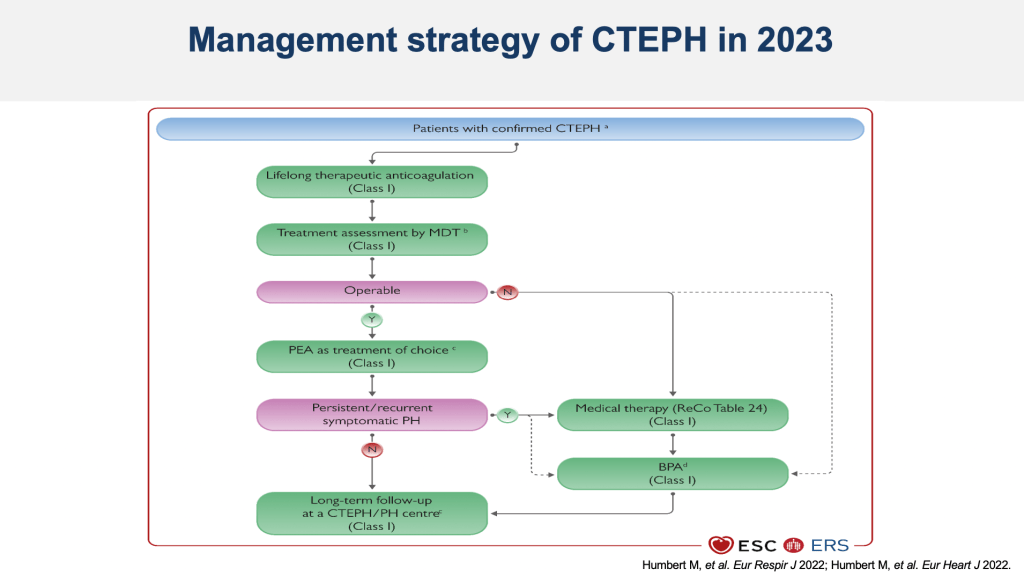

The initial step upon confirming a chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension diagnosis is to propose lifelong therapeutic anticoagulation, which is advised for all patients. The aim of anticoagulation is to prevent the formation of new blood clots. Traditionally, Vitamin K antagonists have been the standard treatment. However, Non-Vitamin K Oral Anticoagulants are increasingly utilized. Despite this, studies have shown that they are less effective than Vitamin K antagonists in cases of Antiphospholipid Syndrome, which is marked by autoantibodies that increase the risk of pulmonary embolism, observed in approximately 10% of patients. Therefore, for patients with Antiphospholipid Syndrome, anticoagulation with Vitamin K antagonists is recommended.

In summary, lifelong anticoagulation is recommended for all patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, and testing for Antiphospholipid Syndrome is advised. Following Marion’s introduction, the treatment assessment is conducted in a multidisciplinary team meeting.

All patients should be evaluated by the chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension team, focusing on multimodal management. The core team should include:

- A surgeon specialized in pulmonary endarterectomy.

- A specialist in pulmonary hypertension.

- A thoracic radiologist.

- An interventionist experienced in balloon pulmonary angioplasty.

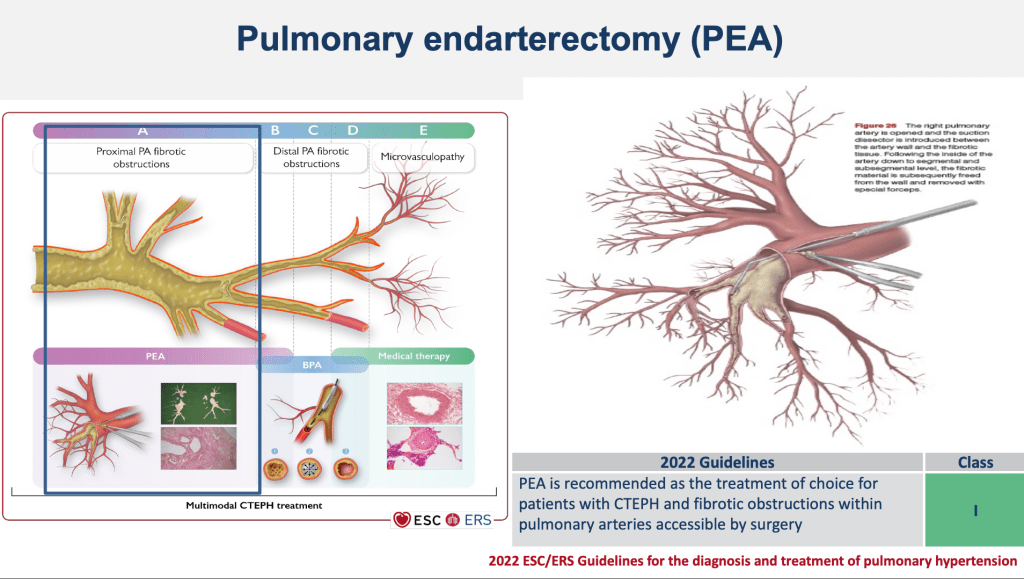

What is the rationale behind multimodal therapy, as mentioned by Marion? In Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension, various regions of obstruction can be identified. These include proximal fibrotic obstruction in the large vessels, fibrotic obstruction of the small vessels, and remodeling of the very small vessels, known as microvasculopathy. Considering the three available treatment options for managing the disease, it’s evident that each treatment targets a different lesion at various levels of the pulmonary vasculature.

Pulmonary endarterectomy is the recommended treatment for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and fibrotic obstruction within the pulmonary arteries that are accessible surgically. This means that for obstructions in the large vessels up to the segmental level, pulmonary endarterectomy is the preferred choice.

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty is recommended for patients who are technically operable, meaning those with fibrotic obstructions involving the small, segmental, and sub-segmental vessels. The principle behind balloon pulmonary angioplasty involves navigating a vessel with an organized thrombus that has some open channels. A balloon is inserted into one of these channels, inflated, and as a result, the organized thrombus is compressed to one side. This action opens the lumen wider by dissecting the media wall, ultimately restoring blood flow past the obstruction.

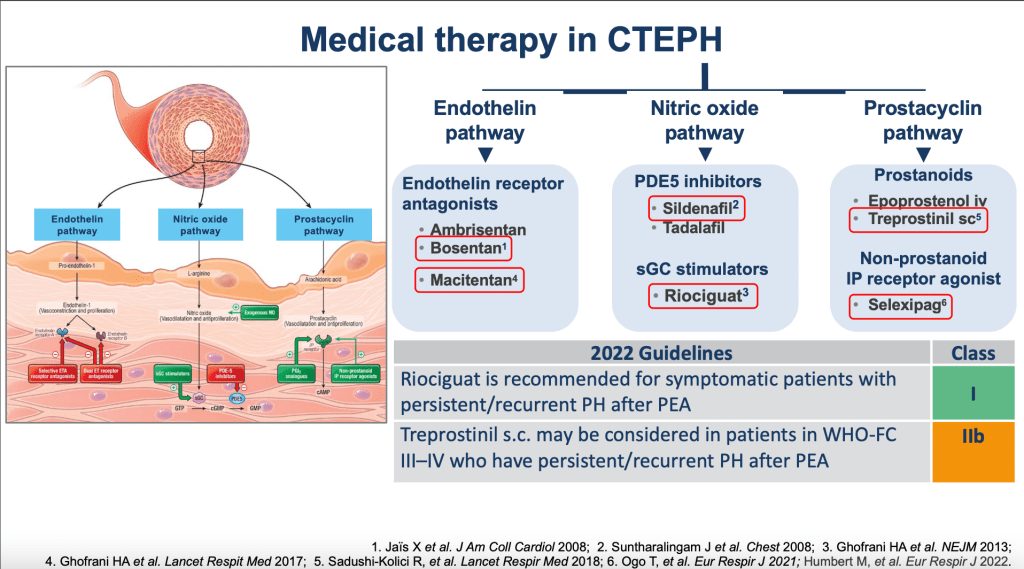

Medical therapy: targets microvasculopathy, the remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature, employing the same treatments used for idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. There are three key pathways involved:

1. Endothelin Pathway:Treatments targeting this pathway include endothelin receptor antagonists, which are used to mitigate the effects of endothelin.

2. Nitric Oxide Pathway: This pathway can be addressed with drugs like sildenafil, a PDE5 inhibitor, or riociguat, a guanylate cyclase stimulator, both enhancing the nitric oxide signaling pathways to relax pulmonary vessels.

3. Prostacyclin Pathway:Medications such as Treprostinil and Selexipag target this pathway, aiming to mimic the vasodilatory effects of prostacyclin.

Regarding the treatment algorithm, the initial step for a patient is to assess operability. If deemed operable, pulmonary endarterectomy is the preferred treatment. This surgery requires general anaesthesia and involves a midline sternotomy to access the heart, with cardiopulmonary bypass being essential to divert blood from the heart and lungs while maintaining oxygenated blood flow to the rest of the body. Complete circulation arrest is necessary to facilitate the surgery, alongside deep hypothermia to lower metabolic rates and protect vital organs. The procedure involves opening the main pulmonary arteries, introducing a dissector between the artery wall and the fibrotic tissue, then carefully removing the fibrotic material with specialized forceps.

Outcomes after surgery: Numerous studies have shown that pulmonary endarterectomy can lead to undercorrection, yet significantly improves symptoms, exercise capacity, and quality of life. Additionally, it results in a reduction of pulmonary arterial pressure and resistance to blood flow, with a three-year survival rate for operated patients at 94%. It’s crucial to reevaluate patients post-surgery, as some may experience persistent symptomatic pulmonary hypertension.

A few points on persistent symptomatic pulmonary hypertension: it refers to patients who, post-surgery, still have pulmonary hypertension and fall within functional class 2 to 4. This includes patients with slight limitations of physical activity (class II), more significant limitations (class III), and those who are unable to perform any physical activity without symptoms (class IV).

In a study examining outcomes three to six months post-surgery for patients with pulmonary hypertension, a notable discovery was made regarding patient management. Despite 85% of patients achieving a functional class of 1 or 2, indicating improved symptoms, over 75% still exhibited pulmonary hypertension, with a mean pulmonary artery pressure exceeding 20 mmHg.

The study further identified a critical mean pulmonary artery pressure threshold: patients with a mean pulmonary artery pressure over 38 mmHg post-surgery experienced significantly worse long-term survival. This finding underscores the necessity for additional interventions, such as medical therapy and/or balloon pulmonary angioplasty, particularly for this group, to enhance survival chances post-surgery.

Moreover, the research highlights the importance of addressing persistent symptoms in pulmonary hypertension patients. For those remaining symptomatic, classified within functional class 2 to 4, and with an mean pulmonary artery pressure over 25 mmHg coupled with a pulmonary vascular resistance exceeding three Wood units, an expanded treatment regimen involving medical therapies or balloon pulmonary angioplasty is advised.

Riociguat is recognized as the approved and recommended treatment for patients experiencing symptomatic pulmonary hypertension following surgery. Additionally, Treprostonil, a prostacyclin analogue, is considered for patients in functional class 3 to 4 who continue to suffer from persistent hypertension post-operatively.

The study further explores the efficacy of combining medical therapy with balloon pulmonary angioplasty for those who remain symptomatic with persistent pulmonary hypertension after surgery. According to the study’s findings, this combination approach significantly reduces pulmonary artery resistance. Moreover, the synergistic effect of medical therapy and balloon pulmonary angioplasty not only mitigates symptoms but also notably improves exercise capacity and overall quality of life.

For patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension or those who cannot undergo surgery due to clots located in the small pulmonary arteries, the two primary recommended treatments are medical therapy and balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Medical therapy includes riociguat, which is the preferred treatment for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension receiving a high level of recommendation. Treprostinil may also be considered for patients in functional classes 3 to 4 with off-label use, including bosentan, macitentan, or sildenafil. Riociguat is recommended for symptomatic patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, though it has a lower recommendation class compared to its use as a first-line treatment. Additionally, a combination of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors plus endothelin receptor antagonists may be considered for patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, with a class 2 recommendation, lower than the class 1 recommendation for riociguat.

Riociguat and balloon pulmonary angioplasty are proposed as first-line treatments for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, both receiving a very high class of recommendation. Studies, including a French study (RATE) and a Japanese study (MRPA), have shown the superiority of balloon pulmonary angioplasty over riociguat in reducing pulmonary pressure and resistance to blood flow in the pulmonary arteries. However, these studies also noted higher incidences of treatment-related adverse events with balloon pulmonary angioplasty than with riociguat.

The primary complication associated with balloon pulmonary angioplasty is vascular injuries, which can occur during the procedure, such as vessel perforation or rupture, especially in smaller pulmonary arteries. These complications can lead to bleeding around the vessel. The risk of balloon pulmonary angioplasty related complications is higher in patients with elevated pulmonary pressure and resistance, indicating that the severity of haemodynamics is a predictive factor for related complications.

In the French RACE trial, we compared the effects of balloon pulmonary angioplasty versus riociguat in treating chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Our findings suggest that pre-treatment with riociguat can significantly reduce balloon pulmonary angioplasty -related complications. Specifically, patients receiving riociguat for six months before balloon pulmonary angioplasty experienced a threefold decrease in complications compared to those treated with balloon pulmonary angioplasty alone. Consequently, we recommend considering medical therapy with riociguat before surgical intervention in eligible chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension patients.

Further studies have shown that combining riociguat and balloon pulmonary angioplasty not only improves exercise capacity and quality of life but also significantly reduces pulmonary pressures and resistance. This combination therapy resulted in a three-year survival rate of 93%, comparable to surgical outcomes.

However, there’s no consensus on the exact therapeutic goals post-balloon pulmonary angioplasty , pulmonary endarterectomy, or medical therapy. Most experts agree that reaching a functional class I or II and achieving near-normal haemodynamics within three to six months post-procedure is desirable. Follow-up, including right heart catheterization and echocardiography, is crucial at three to six months post-intervention to assess treatment effectiveness.

The 2023 treatment algorithm for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension emphasizes initial operability assessment in a multidisciplinary meeting. For operable patients, pulmonary endarterectomy is preferred, with a follow-up at three to six months to evaluate for persistent pulmonary hypertension, at which point additional medical therapy may be considered. Non-operable patients are typically treated with riociguat before considering balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Long-term follow-up is essential to reassess the efficacy of each treatment step.

Thank you for your attention.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Thank you very much, Dr. Jais, for your enlightening presentation on the state-of-the-art multimodal approach to managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Our audience has shown great interest, and a question has arisen: Could you share how widely this new multimodal approach has been adopted? Specifically, do you know in how many countries this approach is currently being utilized?

Dr Jais can’t hear due to technical issues. The question is addressed to Dr Delcroix .

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

The challenge lies in the limited access to technical surgical methods in many countries, leading to an increased number of patients opting for balloon pulmonary angioplasty as it appears more accessible. However, this trend does not necessarily indicate that balloon pulmonary angioplasty is a superior strategy. There’s a critical need to enhance the training and education of surgeons globally. Furthermore, even in countries with surgical access, there’s a noticeable shift towards balloon pulmonary angioplasty in centers proficient in coronary angioplasty due to their existing capabilities, despite the significant differences between the procedures. This situation underscores the importance of integrating cardiologists into multidisciplinary teams to ensure a comprehensive approach to treatment, tailored to the specific needs of each patient. The collaboration among interventional cardiologists or radiologists, surgeons, and pulmonary hypertension specialists within the same center is essential for delivering optimal care. Achieving expertise across these three treatment domains necessitates dedicated centers, as not every cardiology unit is equipped to undertake such specialized procedures. Nonetheless, educational opportunities are more readily available in Europe and the United States, where individuals can easily seek training at specialist centers, despite potential geographical limitations.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Certainly, the key takeaway from the presentation is the issue of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension being frequently under-diagnosed, often resulting in cases being overlooked. This situation poses a significant obstacle for patients, as it hampers their access to appropriate treatment in the absence of a correct diagnosis. I’m interested in your perspective on the referral process to specialized chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension centers that are equipped to offer a multimodal treatment approach. How easy is it, in your experience, for patients to be directed to such multimodal facilities where comprehensive care is available?

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

The referral process in healthcare, influenced by ethical considerations and national practices, varies significantly across countries. In some places, the concept of “patient ownership” prevails, where doctors retain responsibility for patients they diagnose, potentially impeding the referral process. This notion suggests that once a diagnosis is made, the patient remains under the original physician’s care, possibly limiting access to more specialized expertise.

Countries with centralized and well-organized healthcare systems, like France, handle patient referrals more efficiently than others. In contrast, in the United States, even in areas with specialists for rare diseases, referrals may not be as forthcoming. This discrepancy can leave patients without the most knowledgeable care for their specific conditions.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

That’s the aim for the Alliance for Pulmonary Hypertension, to empower patients and assist them in navigating their healthcare journey, even though it can sometimes be challenging. Regarding the number of balloon pulmonary angioplasty sessions required on average for satisfactory results, does this vary based on individual patient conditions and the severity of their pulmonary hypertension?

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

Statistically, most centers conduct four to five balloon pulmonary angioplasty sessions for treating pulmonary hypertension. In these sessions, different vessels are targeted for optimal results. For safety reasons, the initial approach in most centers is to treat one lung at a time. This strategy is adopted to avoid complications such as bleeding in both lungs simultaneously, ensuring that one lung remains fully functional. This precaution allows for effective management of any potential bleeding using other techniques while keeping the other lung operational.

In Japan, which boasts the most extensive expertise in balloon pulmonary angioplasty, the approach can involve conducting minor interventions on nearly all vessels during initial sessions, followed by the use of larger balloons in subsequent sessions. This indicates a diverse range of strategies in the intervention process.

Overall, while the average number of sessions is four to five, specific patient needs can vary significantly. Some patients may require up to nine sessions to achieve satisfactory results, highlighting the personalized nature of the treatment plan based on individual patient conditions and responses to the procedure.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

A question: How many patients require pulmonary hypertension medications after being diagnosed with chronic thromboebolic pulmonary hypertension hypertension and undergoing balloon pulmonary angioplasty? Is there information available on this? Is there reliable data on this matter?

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

Addressing the question of how many patients require ongoing treatment for pulmonary hypertension after surgery or balloon pulmonary angioplasty is complex. Initially, patients were often considered cured post-surgery, with no perceived need for further follow-up or intervention. However, over time, it has become apparent that while surgery can significantly improve exercise capacity and lower pressure measurements, patients are not completely cured. Their condition, when compared to normal levels, remains compromised.

It is increasingly common to continue monitoring these patients closely post-surgery, providing additional treatments as necessary, which may include further balloon pulmonary angioplasty sessions or medication. Evidence suggests that about half of the patients post-surgery still experience a mild level of pulmonary hypertension. The precise haemodynamic threshold at which to initiate further medical or balloon pulmonary angioplasty treatment remains uncertain.

Estimates suggest that around 20% of patients might require some form of treatment after surgery, including medication. In the case of patients undergoing balloon pulmonary angioplasty, the scenario is somewhat different as they typically start with medication before receiving it. The main question for them becomes when it might be appropriate to discontinue medication. This reflects a nuanced understanding of pulmonary hypertension management post-intervention, acknowledging that treatment needs can persist or evolve even after procedural interventions.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Regarding the question of whether it’s advisable to recommend pre-angioplasty medical treatment for all patients, it seems that Dr. JAIS has indeed suggested this approach. It implies that initiating medication before proceeding with angioplasty could be beneficial for patients, potentially enhancing the procedure’s outcomes or stabilizing the patient’s condition in preparation for the intervention.

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

Indeed, the practice of initiating medical treatment before balloon pulmonary angioplasty varies by region. In Europe, it is common to start patients on medication prior to undergoing balloon pulmonary angioplasty. This approach contrasts with practices in Japan, where a significant proportion of patients undergo balloon pulmonary angioplasty without prior medication. This difference underscores regional variations in treatment strategies.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Additionally, are there any genetic risk factors associated with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary Hypertension?

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

There are known genetic risk factors for thrombosis, such as the “Factor V Leiden” mutation and the “prothrombin” gene mutation. However, these do not directly imply a risk for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. In our efforts to identify specific genetic mutations associated with it, we conducted genome-wide analyses but have yet to find definitive mutations. We observed an association with the genetic loci responsible for determining blood groups, suggesting some influence, although chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension does not appear to be a single-gene disease like the conditions associated with “BMPR2” mutations, for example. Identifying the genetic underpinnings of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is challenging, and we have not observed chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension clustering within families, indicating its complex genetic context.

I mentioned that we do not commonly observe chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension occurring in family pairs. Have you encountered any families in which multiple members have been diagnosed and required surgical intervention?

DR. XAVIER JAIS

In our experience, we have encountered only one family where two members developed chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and underwent surgery. Yes, this has occurred, but it was an isolated case involving just one family.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Given that our time is limited, I’d like to ask one final question: Why do specialists sometimes only realize after many years that what was initially diagnosed as pulmonary hypertension is, in fact, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension?

PROF. MARION DELCROIX

Surveys have shown that in some countries, and within some pulmonary hypertension centers more broadly, there is a lack of systematic ventilation perfusion scanning. This has led to delayed identification of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension which is concerning because it is much more treatable compared to pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, we strongly advocate for all centers to incorporate at least perfusion imaging into their protocols to ensure chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is not overlooked.

DR. ANDREAS REIMANN

Thank you very much, Dr Delcroix and Dr. Jais, for your time, and to all our listeners, this webinar will soon be accessible on the pulmonary hypertension knowledge sharing platform. There, you can revisit it and share it with others. We look forward to reconvening on December 12th for our sixth and final webinar of the year, which will focus on the emergence of pulmonary hypertension patient associations and their impact on today’s care landscape. Thank you all for tuning in. Whether it’s evening or day where you are, have a wonderful time. Thank you once again. Goodbye.